1. Introduction

Writing and programming might seem worlds apart: Writing is a creative activity, with goals ranging from entertaining to persuading, from structuring the writer’s thoughts to passing a message to the reader. Programming, on the other hand, is a form of problem solving, in which the programmer starts with a problem, creates a design - a plan of how to solve problem - and then solves this by writing code that a machine can execute. But when one takes a look below the surface, there are also clear similarities to discover. Most strikingly, both writing and programming can be described as the translation of a high-level idea into low level sentences or statements.

In this paper we explore the activities commonly performed in writing and programming with each other highlighting similarities and differences. For example, in programming, formatting and style receive less focus while explicit attention to these has the potential to make code more readable. In programming, code is executed and tested early in the process, while text is often proofread when more finished.

We believe that both fields can learn from a detailed comparison of activities. What does formatting mean in the context of code? Is it important? Can text writing be as iterative and test-driven as code? These are just a few of the questions raised by our side-by-side exploration. Does writing make you a better programmer? What skills underpin both? Can programming learn from writing education?

2. What is writing and what is programming?

So, what is writing? Writing is a way in which humans communicate, using letters and symbols, forming words and sentences. It is used for various different reasons and purposes, including but not limited to storytelling, correspondence and reports of various kinds. The term ‘writing’ is broad, and can be used for activities varying from the motor skill of forming letters to formulating thoughts, feelings and opinions, and to be flawless in the spelling of words and use of grammar rules (Paus, 2014). In this paper we focus on the activity of text composing, regardless the type or genre of the text.

And what is programming? Programming is commonly seen as the process by which a human formulates a problem in such a way that a computer can execute it. It involves understanding the problem, creating a design, writing the syntax of a program - sometimes referred to as coding - and performing maintenance on an existing program (Weinberg, 1985).

3. A high level plan executed in detail

One of the most striking similarities between writing and programming is the fact that in both, there are high-level plans. A murder mystery writer imagines a killer that stabs blond men with stiletto heels; while a programmer imagines an iPad app to manage different bank accounts. These high-level plans are sometimes, but not always, formalized to a certain extent. Writers create designs before they start. A programmer might draw a UML diagram or an architecture plan, and writer creates a table of contents before writing, or uses character sheets and scene descriptions.

Afterwards, these high-level designs need to be translated into very low level constructs: sentences and words for the writers, and methods and lines of code for the programmers. How to approach this is a topic for many methodologies in both writing and programming. Is it better to draft broadly and then iterate, or to take one chapter or feature and make it perfect before adding others? There are people on both sides of the argument in both writing and programming. In writing these two extremes even have terms: Pantsers and plotters.

To help manage the complexity of the translation, in both fields, there are intermediate steps. A writer divides a story into chapters or an essay into sections. These in turn are divided into paragraphs and sentences. Likewise a programmer thinks of classes or objects to contain some parts of a program, which have methods and fields in them.

One aspect where the high-level idea into low-level implementation transformation can lead to problems is when changes need to be made. No text is perfect at the first try; books and stories are often reviewed and rewritten, sometimes assisted by formal reviews. Programmers review each other’s code and suggest changes, or fix bugs in existing code bases. In this adaptation, the high level translating again plays a big role. If writers decide to remove a character from a story, they need to make sure it is deleted from all chapters. If programmers change their architecture, this will result in changes to many classes and methods.

4. A deep dive into activities

So far, we observed the crux of the similarities between writing and programming: the translation of high level ideas into a lower level, the realm of words and letters. We now examine the steps of which the activities of writing and programming consist in more detail, drawing comparisons and highlight differences. The comparison of steps will help us gain insights into both processes better. Where are the procedures similar? Where can we learn from each other? Do we understand striking differences?

There are a number of models of the writing process available, e.g. (Huizenga, 2004), (Paus 2014), (Flower & Hayes, 1981), (Rohman, 1965), all similar in the general picture they paint. The writing process can roughly be divided in three phases: pre-writing, writing, post-writing, which in turn can be divided in two or more sub-phases. Similarly, the process of writing a computer program generally is divided in three phases, resembling the phases in the writing process: design, implement, test, or problem solving, implementing, maintaining (Dale, 1992).

There are more fine grained models too, which we will use here to explore the commonalities between writing and programming as extensive as possible.

| Writing ([Huizenga, 2004](#refs)) | Programming ([Prata, 2013](#refs)) |

|---|---|

| 1. Gathering information | 1. Defining program objectives |

| 2. Selecting information | 2. Designing the program |

| 3. Structuring information | 3. Writing code |

| 4. Translating | 4. Compiling |

| 5. Stylizing the text | 5. Running the program |

| 6. Formatting the text | 6. Testing and debugging |

| 7. Reflecting on the text | 7. Maintaining and modifying |

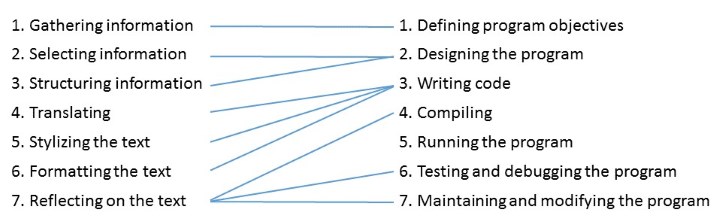

Table 1. Writing and programming in seven steps

In this paper, we use two more fine grained models, for writing we use (Huizenga, 2004) and for programming (Prata, 2013), both consisting of seven steps, as shown in Table 1 (while there are other steps that could be distinguished, we compare these two as an exploration of the activities. We do encourage readers to find other sources, or even define their own steps on one of the two activities and compare those).

Looking at these steps, we immediately observe similarities, which are graphically depicted in Figure 1: Gathering information corresponds to Defining Program Objectives, since both relate to analyzing the environment of the text or program. The following steps are similar too. Selecting information and Structuring information are related to Designing the program, since in both decisions are made about the underlying, often invisible structure of text and program.

After these first three (writing) and two (programming) activities, the differences between the models seem to be getting bigger. Where in programming we see the third step Writing code, in writing, there are three separate steps related to getting the words in their final form: Translating, Stylizing the text and Formatting the text. This level of detail in could be one of the areas where programming could learn from writing, maybe it is a good idea to regard these steps as different activities in programming too?

In programming on the other hand, there is Compiling and Running the program. This represents a difference between writing and programming, in programming, the programmer gets feedback very early on whether the program text is executable, during compiling. Furthermore, they get feedback on whether the program is working as intended. One could argue that, in writing, the first ‘execution’ of the program happens when someone else reads it, and that it is thus takes longer to know whether a text has the desired intend. Of course writers themselves can read the text and ‘execute’ it, but the question is if that really executes the text alone. If the writer reads the text, can they refrain from also taking into account the context and intentions?

In the remaining sections, we will first discuss the similarities in the first and last steps, and then the differences mainly occurring in the middle parts.

5. Similarities

In this section, we zoom in on the similarities in the steps, which mainly occur in the beginning and end of the process.

5.1 Getting to know the context

The first steps in both fields concern the context of the text and code. What needs to go in? Who is the target audience? What do I want my text to convey, or my program to do?

When starting a new project, assignment, or exercise in writing or programming, the first step is setting of the goals. What subject must the text be about, or what problem must the computer program solve? What kind of text does the writer wants, or has, to write; a fictional story, recipe, or maybe a blog on his website? Who is the intended audience and what are the demands of a possible client or reader? With these goals in mind, writers start gathering information about the subject. They may use various kinds of sources like their own imagination and emotions, experiences of others, information found in external sources like books, videos and websites about the subject.

In programming, the gathering of information is a field of research in itself: requirements engineering. There are numerous different techniques for eliciting the requirements from a user (Kotonya, 1998), (Sommerville, 1997), (Pohl, 2010).

In this context, we are mainly talking about the process in which software is made for a customer. Of course, there are also projects that start because programmers really want to make something for themselves, without fixed requirements. Even in that case, a first step will often be gathering information, such as which programming language, library or API to use, or what similar system might exist.

5.2 Making plans

After the exploration of the context, there is a focus on designing the artifact. What will the storyline be? What is the structure of the argumentation? What characters are going to appear in what chapters? These contemplations could be comparable to questions like: What will the architecture of our system be? What classes and methods will we have? or What programming paradigm fits our problem best?

From all the gathered information the writer selects the useful information for this specific task, after or even during the information gathering process. Writers choose which information is relevant for the reader to understand the story line and also fits the chosen subject of the text.

The selection of relevant information too is a skill important in programming, again, especially in the commercial setting of creating software for an internal or external costumer. Different features of the program to be created are classified by importance, for example using the MoSCoW model (Clegg, 1994), or user stories are created, which are then grouped into sprints. By categorizing important features, programmers are deciding what information is most important for the program.

In writing, the gathering of information can be more vague, especially for writers of fiction, maybe the gathering is more of inspiration than of information. After gathering information and selecting the relevant parts, the writer organizes all information in a way that suits his habits in writing and fits the requirements of the text identified by the goals.

Ideas can be collected and structured in various multi- or one-dimensional ways. For example using a mindmap which represents relations between concepts, arguments and/or characters. In case of a recipe or manual writers may use a flowchart to structure their ideas. They may also provide short descriptions for characters, situations or scenery. Once gathered and organized ideas, the writer has an abstract representation of the text in mind.

Structuring in programming means creating a high-level design for a program. In this phase, design decisions are made about the program, such as, for example: what programming language and database system will be used? What type of software architecture will we follow, for example a model-view-controller or a micro-services setup. Lower level decisions are also made, such as what classes are needed and how they will related to each other. That is often done using a class diagram or an entity relationship diagram when data is being structured.

5.3 Translating

In writing, the step following Structuring information is Translating: transferring abstract concepts to linear natural language. While putting the design into sentences and words, the writer has to abide by rules. These rules might be rules of the language, for example, words need to be spelled correctly and sentences must be correct grammatically, but may also depend on the context of the text, for example in a scientific article, references have to be correct and in an persuasive argument, the text structure should be logical.

Similarly, the programmer now moves from the whiteboard to the keyboard, to start produces lines of code which implement the high-level design. Like in writing, the programmer needs to do so while applying rules. For example, code must be syntactically correct in order to be compiled or interpreted. In addition, some languages have stricter rules about what is allow, like typing rules that the programmer must obey.

According to (Flower & Hayes, 1981), in this process, the writer has to juggle different specific demands of written language varying from generic and formal, syntactic and lexical to the motor tasks of forming letters or typing on a keyboard. For example, when a writer has difficulties with the spelling of the words, this process will use up so much of their working memory that they have no room to think about the structure of a paragraph. This high ‘cognitive load’ has been studied in the context of programming, and programming education, as well (Harms, 2013), (Sweller, 2016), (Shaffer et al., 2003)}

5.4 Reflecting and Reviewing

We will reflect on differences in the remaining steps in the next section, but for now, let’s move to the final step of writing and the sixth of programming: Reflecting on text and Testing and Debugging and Maintaining and modifying the program.

After the text is written - and often also during the writing process - the writer reflects on their process and product. Are the goals met? Have I lived up the expectations of the assignment or client? Is my text readable?

Likewise a programmer reflects: Does my program function as expected? Is this code well-structured and free of code smells? Here, of course, there is an interesting difference between writing and programming, since a programmer can party rely on the computer to validate their program. Firstly of course by the compiler and the type-checker in statically typed languages, and later by an interpreter and a runtime. Furthermore, programmers increasingly often use tests to ensure the correctness of their programs. To find bugs, but also to ensure code quality, programmers sometimes use static analysis tools (Johnson et al., 2013).

Failure to compile, to pass all tests, or too many code smells might impose a need for a revision of the source code. This type of product-inherent warnings for review is not present in writing texts. While this is a clear benefit, this might also reduce the need for or interest in manually reviewing the source code, not for functionality, but for readability. Recent systems for collaborative programming, like GitHub and their support for code review via pull requests have spurred interest in code reviews for readability and maintainability.

These steps seem very similar, as they concern verifying that the text or program performs the task it needs to. However, programming has a seventh step, in which the program is maintained. Often, of course, programs are updated after they have been deployed, while books or articles typically remain the same.

6. Differences

In this section we highlight differences between the models of Huizenga and Prata. As said, there exist other, different models, which would lead to different comparisons. These two list are our choice, but we encourage others to make more, and different comparisons.

In our lists, we observe that not all steps are as similar as the first and last few steps. In the middle, we observe more differences than similarities, which we will elaborate on in this section. The most important difference is that in programming, making the source code is just one step: Writing the program, while in writing, there are two additional steps related to the stylizing and formatting of the text. In this section we will elaborate on what these steps mean in writing and how they could be interpreted in programming.

6.1 Stylizing text

When the ideas of the writer have been translated into text, a writer will apply rules of style. For example, an essay has a formal style with longer sentences and advanced jargon, while a children’s book is written in a cheerful style using simpler words. It is generally agreed upon that in order to write a good document, the writer has to apply a style to an entire document consistently, otherwise the text might be harder to understand, or less enjoyable to read.

Style can also depend on the intended audience of a text. When writing a letter, for example, the choice of style is related to the intended addressee. The style of a letter directed towards a loved one differs in various ways from the style of an job application letter.

In addition to these type of styles, prescribed by the goal of the text, many writers have their own personal style. This personal style might consist of the heavy use of adjectives to describe scenery, or the strict avoidance of multiple clauses. Other examples are the use of different perspectives, such as first or third person, or the omniscience of a narrator. Such a personal style will automatically be applied by the writer throughout the entire text, and therefor differs from the above described styles imposed on the writer.

As the French writer Raymond Queneau shows in (Queneau, 1981), many styles can be used to communicate the same content. By using different styles, the atmosphere of the text can strongly vary. Writers often experiment with styles to find out which one fits the intended feeling best.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show two exercises from Queneau (source of translation); Surprise and Hesitation. Readers can check for themselves that on every singly line, in every single sentence, the writer has stuck to the chosen style. This reflects in specific words (e.g. ‘how’ in Surprise and ‘but’, ‘don’t really’ in Hesitation), types of sentences (short and firm in Surprise and long and intermittent in Hesitation) and punctuation (exclamation marks in Surprise and dots and question marks in Hesitation).

How tightly packed in we were on that bus platform! And how stupid and ridiculous that young man looked! And what was he doing? Well, if he wasn’t actually trying to pick a quarrel with a chap who–so he claimed! the young fop! kept on pushing him! And then he didn’t find anything better to do than to rush off and grab a seat which had become free! Instead of leaving it for a lady!

Two hours after, guess whom I met in front of the gare Saint-Lazare! The same fancypants! Being given some sartorial advice! By a friend!

You’d never believe it!

Figure 2. Queneau’s Exercises in Style: Surprise

I don’t really know where it happened…in a church, a dustbin, a charnel-house? A bus, perhaps? There were…but what were there, though? Eggs, carpets, radishes? Skeletons? Yes, but with their flesh still round them, and alive. I think that’s how it was. People in a bus. But one (or two?) of them was making himself conspicuous, I don’t really know in what way. For his megalomania? For his adiposty? For his melancholy? Rather…more precisely…for his youth, which was embellished by a long…nose? chin? thumb? no: neck, and by a strange, strange, strange hat. He started to quarrel, yes, that’s right, with, no doubt, another passenger (man or woman? child or old age pensioner?) This ended, this finished by ending in a commonplace sort of way, probably by the flight of one of the two adversaries.

I rather think that it was the same character I met, but where? In front of a church? in front of a charnel-house? in front of a dustbin? With a friend who must have been talking to him about something, but about what? about what? about what?

Figure 3. Queneau’s Exercises in Style: Hesitation

Prata’s list of steps of programming does consist the style of a program, which of course makes it interesting to think of what exactly ‘style’ would mean in the context of a program. Some authors who have explored different styles in programming, for example (Lopes, 2014). Her book describes a number of different styles to calculate term frequency, including continuation passing style, and functional style. However, if we look at the steps in programming, we feel this is more related to Designing the program than it is to stylizing.

There are however several places in source code where developers have freedom in giving ‘a style’ to their code. One of the concepts related to style could be whether or not the code has comments. Some programmers feel that good code should explain itself, but many also agree that comments are a good coding practice. The most extreme form of this style might be the idea of literate programming introduced by (Knuth, 1984). He envisioned a style of programming in which program statements are interspersed with documentation in a natural language, to ease in understanding the program. However compelling the idea of literate programming, in practice it is not used widely, with the potential exception of ‘notebooks’ like Mathematica or iPython.

Another area where a style can be expressed, is when programmers are selecting keywords.

Choosing how to name a keyword can be seen as a literary activity, since the programmer is

defining the role of a variable with meaningful words. Arguably, the programs x := 5 and

total := 5 are executed in the same way by a compiler, but not by the brains of future readers.

A more elaborate example is shown in Figures 4 and 5. These two programs could be seen as

different styles of the same programs, embodying the difference between simply presenting

facts and taking the reader along in a story of what is happening.

decimal x = decimal.Parse(Console.ReadLine());

decimal y = decimal.Parse(Console.ReadLine());

deecimal area = x * y;

Console.WriteLine(area);

Figure 4. A program that prints the area of a rectangle

// this program calculates the area of a rectangle

decimal lengthSide = decimal.Parse(Console.ReadLine());

decimal widthSide = decimal.Parse(Console.ReadLine());

decimal area = lengthSide * widthSide;

Console.WriteLine(area);

Figure 5. A second program printing the area of a rectangle

While these differences might seem small, keywords are known to play a large role in source code, as about three quarters of characters in a code base consist of identifiers (Lawrie et al., 2007). Better identifier names correlate with improved program comprehension. For example, (Lawrie et al., 2006) reports on a study performed with over 100 programmers, who had to describe functions and rate their confidence in doing so. Their results show that using full word identifiers leads to better code comprehension than using single-letter identifiers, measured by both description rating and by confidence in understanding.

Here, observing differences between writing and programming leads to questions about stylizing programs. Could we envision a class of programs which, like fairy tales, always have a similar style in all their occurrences? What is a surprising program, or a hesitant one? Do they compile to the same output? And can we think of a group of programs which, like letters, share a goal, but could be stylized in different ways? What is the difference between a personal style and one imposed by the environment or audience?

We believe contemplating these type of questions will make programming as a field richer and we encourage readers to come up with style of programs they like to see.

6.2 Formatting text

Another step that is missing in Prata’s programming steps is formatting. In writing, formatting means the writer layouts text, for readability or aesthetic reasons. Formatting text is typically one of the last steps in the writing process. A few activities which are commonly performed while formatting are adding images and figures to make the text more attractive or easier to understand. Or, when the writer wants to draw attention to a specific part of the text, they can use add emphasis with font options, such as making text bold, italic or changing the font color.

Sometimes, for example when the text is being published by a publisher, the formatting step might be done, partially of fully, by someone other than the writer.

Figure 6 shows two versions of a diamond poem: in the first draft the text is formatted using practical constraints, the writer has only outlined the poem by its requirements (number of characteristics of the animal per line), the final version of the text has a different shape (diamond), different font, different background color and there are images added.

Formatting, like stylizing, is an particular interesting concept in programming, since it is often seen as an afterthought. This is underlined by the fact that there is no formatting step in Prata’s model.

Again of course the question arises that formatting means in the context of programming. In some languages, programmers have no freedom in some aspects of formatting. For example, in Python the indentation level of the statements is significant, meaning that code in which, for example, the body of a loop is not indented does not work.

Most other languages do not have formatting requirements that strict, but many have formal of informal code conventions, from which a deviation is seen as a bad habit. Some people argue that these now informal formatting rules should be made mandatory. For example, in ‘The best software writing’, Ken Arnold argues that:

For almost any mature language […] coding style is an essentially solved problem. I want the owners of language standards to take this up. I want the next version of these languages to require any code that uses new features to conform to some style.

More than tools used for natural language writing though, tools for programming, called integrated developments environments (IDEs) have features that format code automatically. Recently, researchers have successfully attempted to learn formatting conventions from a code base, in order to increase its consistency automatically (Allamanis et al., 2014).

Despite the existence of these required, advised or automated formatting measures, programmers do still have some freedom in the formatting of their source code. As an example, consider the two code snippets in Figure 7.

Both programs are following code conventions, however, they feel different. The distance between the declaration and the use of a variable might influence the understandability of a piece of source code, or simply the enjoyment with which someone would read it, underlining the importance that formatting can have on a program, even within the limited freedom that a programming language offers, compared to natural language.

int a; int b;

int b; int x;

int y;

int x;

int y; int b = x + y;

int z;

int a;

int b = x + y; int z;

int a = b + z;

int a = b + z;

Figure 7. Two similar programs with different formatting

Finally, there is a way in which formatting in programming is richer than in writing, and that is syntax highlighting: the coloring of lexical tokens in source code text according to a certain categorization. For example, coloring keywords blue, variables red and operators black. Experiments done with syntax highlighting have shown that it can reduce time needed for a given task and reduces context switches. This effect is greater in novice programmers than in programmers with more experience (Sarkar, 2015). It would be interesting to see if effects like this exist in natural language comprehension as well, for example by using colors to identify part of speech.

6.3 Compiling and running code

A final, seemingly, difference we want to highlight is that in programming, code can be type checked, compiled and ran during the development process. While in writing of course writers themselves can read the text, and distribute drafts to people, this is not as easy and effortless as hitting a compile button.

This leads to the deep questions of what does it mean for a text to run? Maybe this can only happen in the mind of a reader? Or could we envision an algorithm that mimics this, and predicts the thoughts and even emotions of future readers?

There are tools that attempt this somewhat, a simple spell checker comes to mind, or the more advanced Hemmingway app which highlights bad writing style like long sentences and passive voice. While these are useful, they do not seem to resemble the execution of a text in a human’s brain very closely yet.

7. Implications

The above of course raises the question how this all helps programmers or writers or both. Given enough layers of abstraction, all things are similar. I am an object, the computer on which I type this is one too. What does that teach us? We however think there are some important takeaways from the comparison between writing and programming that we can learn from.

7.1 Metaphors shape thinking

Firstly, the way we view programming impacts the field. We personally have found the plotters and pantsers views very appealing also for programming, some people like planning, while others want to see where the code takes them. The same person might even be plotting sometimes and ‘pantsing’ in other situations. The way programming is currently seen by many, through the metaphor of software creation as “software engineering” feels as designed by and for plotters. Here’s a though: If we had viewed programming more alike writing from the start, would we have come to agile design methodologies sooner?

7.2 Impact on education

It is not just the way we think about programming, but also the way we teach it that is greatly influenced by the way we see our field, the research programmes we view it through. If we see programming as writing, can we learn from writing education? This question warrants a full paper, but there are a few directions we see we can learn from. Could we apply these methods to programming education too?

7.2.1 Observational learning

For example, the use of observational learning, where a teacher or peers demonstrates a task before learners attempt it. In writing education in fact, teacher modeling is the most prevailing way of using models for learning. Usually in the instructional phase (Koster & Bouwer, 2016). In this teaching method the teacher thinks out loud, they explain and demonstrates parts of the writing task. Pupils are expected to adopt the line of reasoning while executing the writing task. It is shown an effective instructional method to teach writing strategies, see e.g. (Fidalgo et al., 2015), (Graham et al. 2005), (Koster & Bower, 2016).

Modeling is not limited to one or some parts of the writing process, but is a useful method for instruction in strategies for every step of the process, from gathering information to reviewing the text, see also (Aldewereld & Hermans, 2017). Usually the teacher functions as a mastery model, although it is shown that observing coping models (which are not flawless, but experience difficulties in the execution of the task and show how they cope with these difficulties) raises the self-efficacy of the pupils and enhances their performance more effectively. For weaker pupils, observing coping models is more beneficial, for better learners observing better models is (Braaksma et al., 2002), (Braaksma et al., 2004), (Koster & Bower, 2016), (Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 1999).

This effectiveness of this method is explained by the existence of the mirror neuron system in our brain. This system makes the brain demonstrate identical neural activity when we observe others performing a task as if we perform the task ourselves, see e.g. (Rizzolatti, 2005), (Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004). In this way, the brain already ‘learns’ how to perform a task, and primes the execution of similar tasks.

7.2.2 Course integration

Writing can be taught in isolation, but can also be taught in combination with other topics, for example, when pupils are writing an essay about modern history. Research has shown that this type of integration is beneficial for both of the topics taught. For example, Romance en Vitale combined science courses for grades 1 and 2 (ages 6 to 8) with reading and writing assignments, such as writing an overview of learnings and a diary, and reading are appropriate science materials. These children performed significantly better than a control group on both science and reading (Vitale & Romance, 2012).

In another study compared the effectiveness of two different methods of teaching science: one aimed at just teaching science, a second on combined with reading and literacy. In this latter group the kids learned to think, speak, read and write like scientists. The control group, which is often used and designed by the same university was aimed at performing and learning about experiments. The results showed that the experimental group had a better understanding of what science is, a better understanding of the basic concepts and also they identified more as scientist (Girod & Twyman, 2009).

This last study could prove especially interesting for programming education, as it also could help a broader group of kids identify as programmers!

8. Concluding remarks

In this paper, we aim to draw a comparison between writing and programming by comparing their goals and challenges. Looking from a distance, both can be seen as having a very high level idea and representing that with low level constructs. We observe that some steps as defined by writing and programming authors are similar, Structuring information is like Designing program, in that for both the performers need to take in information and decide on how to structure it to fit their goal best. We would love to explore our beliefs further in the future, for example by conducting a think aloud study with people writing or programming, or by placing people in an fMRI scanner and measure their brain activity.

Other steps present in writing, like Stylizing and Formatting, are not commonly described and studied in programming, and we hope our paper leads to more discussion on these activities in programming. Is adding whitespace style or is it formatting? Having clearly, agreed upon definitions like in writing can ease teaching and communication on these type of topics. Can we learn from best practices in writing? The other way around, programming has explored the step of reflecting and adapting in more detail probably due to the collaborative nature of modern day programming projects. There writing could be inspired by ideas like pull requests and formal code reviews.

There are also places where writing could be inspired by programming: Programmers attempt to get feedback from the “environment” earlier than writers, by compiling and running their program. Can writers similarly somehow have a machine reflect on their text while they are still writing?

There are certain things that we consider out of scope for this paper. For example, in the above, we have followed (Huizenga, 2004) and (Prata, 2013) in their linear representation of writing and programming, but often, in both domains, the processes can also be represented as a cycle. For example, in writing the consensus is that writers continuously switch between the steps of the process as described above. In programming a cycle that is often referred to is Beck’s Test Driven Development cycle (Beck, 2003). We presented the cognitive processes and skills in a linear way, but the reality is not so strict. The process is not even cyclic, although this fits reality more than a linear representation. In reality the writer or programmer switches between writing or programming stages freely and uses different skills throughout the entire process.

Future work in exploring this comparison should surely examine the cyclic (or even messier) order of steps in more detail. There is one more observation: the fact that the activities are similar leads us to think that also the skills and the way we teach could learn from each other.

-

Allamanis, M., Earl T. Barr, Christian Bird, and Charles Sutton (2014). Learning Natural Coding Conventions. In Proceedings of the 22Nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering (FSE 2014). ACM.

-

Arnold, K. (2005). The Best Software Writing I. 1–6 pages.

-

Beck, K. (2003). Test-Driven Development: By Example. Addison-Wesley.

-

Braaksma, M. AH, Gert Rijlaarsdam, and Huub Van den Bergh (2002). Observational learning and the effects of model-observer similarity. Journal of Educational Psychology 94, 2 (2002), 405.

-

Braaksma, M. AH, Gert Rijlaarsdam, Huub Van den Bergh, and Bernadette HA M van Hout-Wolters (2004). Observational learning and its effects on the orchestration of writing processes. Cognition and Instruction 22, 1 (2004), 1–36.

-

Clegg, D. and Richard Barker (1994). Case Method Fast-Track: A Rad Approach. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc., Boston, MA, USA.

-

Dale, N. and Chip Weems (1992). Introduction to Pascal and Structured Design: Turbo Version (3rd Ed.). D. C. Heath and Company, Lexington, MA, USA.

-

Fidalgo, R., Mark Torrance, Gert Rijlaarsdam, Huub van den Bergh, and Ma Lourdes Álvarez (2015). Strategy-focused writing instruction: Just observing and reflecting on a model benefits 6th grade students. Contemporary Educational Psychology 41 (2015), 37–50.

-

Flower, L. and John R Hayes (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College composition and communication 32, 4 (1981), 365–387.

-

Girod, M. and Todd Twyman (2009). Comparing the added value of blended science and literacy curricula to inquiry-based science curricula in two 2nd-grade classrooms. Journal of Elementary Science Education 21, 3 (2009), 13–32.

-

Graham, S.,Karen R Harris, and Linda Mason (2005). Improving the writing performance, knowledge, and self-efficacy of struggling young writers: The effects of self-regulated strategy development. Contemporary Educational Psychology 30, 2 (2005), 207–241.

-

Harms, K. J. (2013). Applying cognitive load theory to generate effective programming tutorials. In 2013 IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages and Human Centric Computing. 179–180.

-

Huizenga, H. (2004). Taal & didactiek. Stellen. Wolters-Noordhoff.

-

Johnson, B., Yoonki Song, Emerson Murphy-Hill, and Robert Bowdidge (2013). Why Don’t Software Developers Use Static Analysis Tools to Find Bugs? In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE ‘13). IEEE Press

-

Knuth, D. E. (1984). Literate programming. Comput. J. 27 (1984), 97–111.

-

Koster, MP and IR Bouwer (2016). Bringing Writing Research into the Classroom: The effectiveness of Tekster, a newly developed writing program for elementary students. Ph.D. Dissertation. ICO.

-

Kotonya, G. and Ian Sommerville (1998). Requirements Engineering: Processes and Techniques (1st ed.). Wiley Publishing.

-

Lawrie, D., Henry Feild, and David Binkley (2007). Quantifying identifier quality: an analysis of trends. Empirical Software Engineering 12, 4 (2007), 359-388.

-

Lawrie, D.,Christopher Morrell, Henry Feild, and David Binkley (2006). What’s in a Name? A Study of Identifiers. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension (ICPC ‘06). IEEE Computer Society

-

Lopes, C. V. (2014). Exercises in Programming Style. Chapman & Hall/CRC.

-

Hermans, F., Marlies Aldewereld (2017). Writers and programmers, a marriage with benefits. (under submission)

-

Paus, H. (2014). Portaal: Praktische taaldidactiek voor het basisonderwijs. Uitgeverij Coutinho.

-

Pohl, K. (2010). Requirements Engineering: Fundamentals, Principles, and Techniques (1st ed.). Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated.

-

Prata, S. (2013). C Primer Plus (6th ed.). Addison-Wesley Professional.

-

Queneau, R. and Barbara Wright (1981). Exercises in style. Vol. 513. New Directions Publishing.

-

Rizzolatti, C. (2005). The Mirror Neuron System and Imitation. Perspectives on Imitation: Mechanisms of imitation and imitation in animals 1 (2005), 55.

-

Rizzolatti C. and Laila Craighero (2004). The Mirror-Neuron System. Annual Review of Neuroscience 27 (2004), 169–92.

-

Rohman, D. G. (1965). Pre-writing the stage of discovery in the writing process. College composition and communication 16, 2 (1965), 106–112.

-

Sarkar, A. (2015). The impact of syntax colouring on program comprehension. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group (PPIG 2015). 49–58.

-

Shaffer, D., Wendy Doube, Juhani Tuovinen (2003). Applying Cognitive Load Theory to Computer Science Education. In Proceedings of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group.

-

Sommerville, I. and Pete Sawyer (1997). Requirements Engineering: A Good Practice Guide (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY, USA.

-

Sweller, J. (2016). Cognitive Load Theory and Computer Science Education. In Proceedings of the 47th ACM Technical Symposium on Computing Science Education (SIGCSE ‘16). ACM.

-

Vitale, M. R. and Nancy R. Romance (2012). Using In-Depth Science Instruction to Accelerate Student Achievement in Science and Reading Comprehension in Grades 1-2. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 10, 2 (2012), 457–472.

-

Weinberg, G. M. (1985). The Psychology of Computer Programming. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY, USA.

-

Zimmerman, B. J. and Anastasia Kitsantas (1999). Acquiring writing revision skill: Shifting from process to outcome self-regulatory goals. Journal of educational Psychology 91, 2 (1999), 241.